Houston is one of the fastest-growing, most dynamic cities in the United States. Now boasting 2.2 million residents and encompassing 630 square miles, the city continues to grow to the west and northwest where land is available. This land, called the Katy Prairie, is critical to wildlife and to people.

In addition to creating habitat for wildlife, the prairie-wetlands, ranches, creeks, and other green spaces on the prairie slow water heading downstream towards Houston, providing time for floodwaters to recede. As these prairie lands shrink, so does the ability to protect downstream citizens. This is why the Coastal Prairie Conservancy is working with others to protect these lands. In addition, we are working with others on programs that will help alleviate future downstream flooding.

We believe in safeguarding wildlife. We believe in fostering a healthy community. We believe in Houston.

Houston keeps paving over rain-absorbent Katy prairie

At the far west end of Houston along the Katy Freeway, where the concrete city gives way to bigger sky and taller grass, signs advertising new master-planned communities greet you before anything else, pointing left and right to new neighborhoods going up where prairie used to be.

While Harris County officials say the new development is not happening in the floodplain — since it is built atop mounds of fill — and will not increase flood risk downstream because of drainage requirements, such as detention ponds, the fact remains that development covers the prairie sponge with concrete.

Prairies serve as natural flood mitigation, absorbing more water than other types of land, retaining water in their natural depressions and slowing down the flow with their tall grasses.

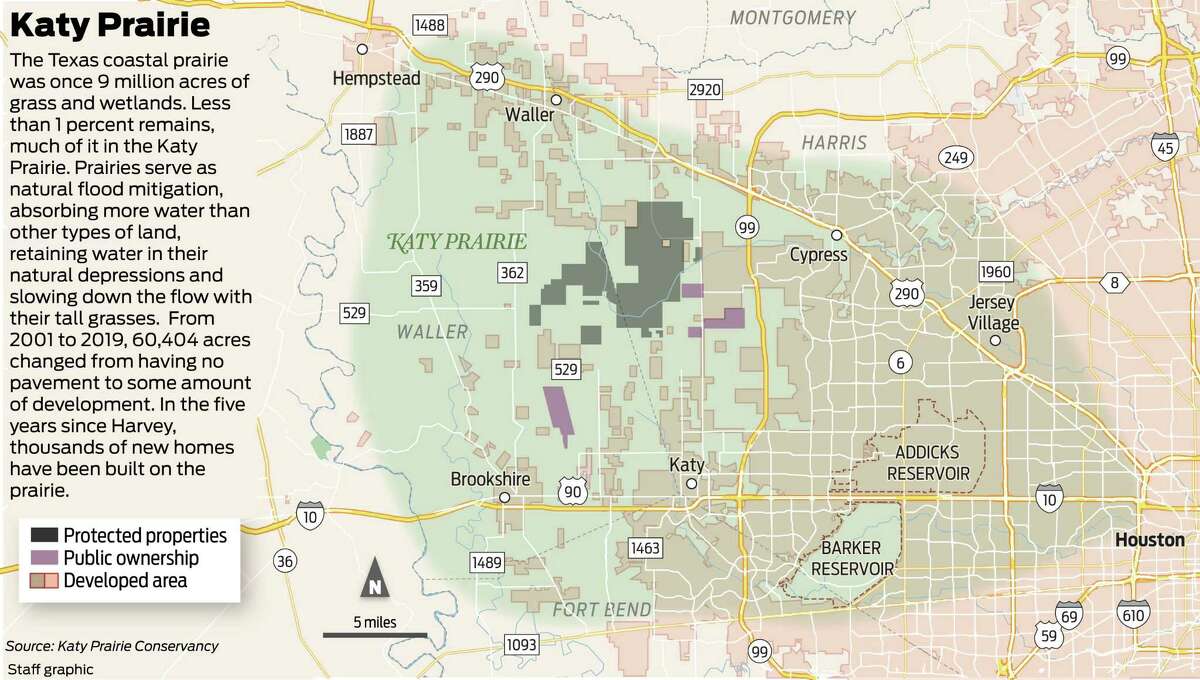

The Houston region used to be covered in that type of vegetation, back when the state’s coastal prairie was 9 million acres of grass and wetlands. Less than 1 percent of coastal prairie remains in Texas, much of it in the Katy prairie — an area difficult to define these days since it continues to shrink, but in the 1990s was roughly bounded by the Brazos River, U.S. 290, Highway 6 and Interstate 10.

After Hurricane Harvey, then-Harris County Judge Ed Emmett took a strong position on the prairie in an opinion piece published in the Houston Chronicle.

“Officials at all levels should commit to preserving the Katy Prairie as a national or state park or nature preserve,” Emmett wrote. “That single act might do more to protect our community than any other. It will not only reduce future flooding, it will send a clear signal that we have a new attitude — that we recognize the value of maximizing natural green space and we understand the importance of allowing waterways to function without interference.”

That has not happened.

In the five years since Harvey, thousands of new homes have been built on the prairie and former rice farms above the Addicks and Barker reservoirs.

The reservoirs operated as intended in Harvey, but homes upstream and downstream of Addicks flooded anyway, prompting lawsuits that still are being litigated. The flooded homes were not a surprise to those who predicted development within the reservoir and upstream of it — combined with extreme rainfall — would lead to disaster.

Today’s new development continues a trend that has been underway for decades.

Between 2010 and 2020, nearly 100,000 people moved into the Harris County portion of the Addicks Reservoir watershed — a 138-square-mile area that drains into the reservoir — increasing the population there from 295,694 to 390,402, according to the Harris County Flood Control District.

In the Katy prairie area, from 2001 to 2019, 60,404 acres changed from having no pavement to some amount of development.

Today’s new development continues a trend that has been underway for decades.

Between 2010 and 2020, nearly 100,000 people moved into the Harris County portion of the Addicks Reservoir watershed — a 138-square-mile area that drains into the reservoir — increasing the population there from 295,694 to 390,402, according to the Harris County Flood Control District.

In the Katy prairie area, from 2001 to 2019, 60,404 acres changed from having no pavement to some amount of development. https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/10938241/embed

High-intensity and medium-intensity development have increased by 57 percent and 52 percent respectively, while the amount of undeveloped land has decreased by 10 percent, according to an analysis by the Chronicle.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/fSn99/1/

What you need to know to understand flooding

People often misunderstand when rainfall is described as “100-year” or “500-year” storms.

For the general public, one underlying question to ask is pretty straightforward: how many inches of rain are we preparing for?

For example, the recently completed Project Brays in Meyerland was built to withstand a 100-year storm, or 13.2 inches of rain.

That, however, is the previous 100-year storm standard.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which defines the standard, recently increased the rainfall amount based on the storms Houston has experienced the last couple decades.

For example, Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 dropped 25 inches of rain in some parts of town. The 2015 Memorial Day flood resulted from 11 inches of rain in 3 hours. The next year’s Tax Day flood averaged 12 to 16 inches of rain across the city in 12 hours. Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019 exceeded 30 inches over three days. And Hurricane Harvey in 2017 dumped 47 inches over parts of Harris County over four days.

So now, in Harris County, NOAA says local governments should plan for 17 inches of rain to protect against a 100-year storm. A 500-year storm is now 25 inches of rain in 24 hours, instead of 18.9 inches.

Not all local governments have agreed to the changes, but many have, including Harris County, Fort Bend County and the city of Houston.

The new formula does not include projections for how climate change will increase future storms.SEE MORE

Preservation

Between the new subdivisions, you can see what the ground used to look like: flat and wild, covered in a variety of bright flowers and deep-rooted native grasses. The vegetation is not curated or landscaped for humans, instead following nature’s design in the form of wetlands and a sprawling indiangrass preserve. It also is home to many types of wildlife, including frogs, butterflies and 15 different kinds of ducks.

There is a reason this particular land has not been turned into housing or strip shopping centers — it is not even for sale — and it is not because no one has thought to develop it yet.

PROTECTING PRAIRIE: Katy Prairie Conservancy takes on a new name as its reach grows

The nonprofit land trust Coastal Prairie Conservancy, known as the Katy Prairie Conservancy until recently, has been working since 1992 to protect what is left of the Katy prairie. Today, it protects 30,000 acres of prairie and directors hope to acquire another 20,000.

Mary Anne Piacentini, Katy Prairie Conservancy president, talks at the Indiangrass Preserve, 31975 Hebert Road, Tuesday, July 20, 2021 in Waller. (Melissa Phillip / Houston Chronicle) / Conservancy instructor Jaime Gonzalez (left) teaches kids about bees at the Katy Prairie Wednesday, June 29, 2016. (Steve Gonzales / Houston Chronicle)

David Nelson, a rice farmer who lived in the Katy prairie area his entire life, sold some land to the conservancy and some to developers, farming his last crop in 2010.

When he finally decided to move away, it was partly because of the traffic and partly because of flood risk.

“As Houston continued to come this way, developers got to building houses,” Nelson said. “A house and a driveway and a street don’t absorb much water. In fact, it accelerates the runoff.”

Nelson could see the new subdivisions around his property were changing drainage patterns and he knew it was only a matter of time before his home started flooding.

“It’s going to come down past my house toward FM 529 a whole lot faster,” Nelson said. “I can speculate what’s going to happen. I’m just glad we don’t live there anymore.”

Long before Harvey, people like Nelson watched the prairie and rice farms disappear and knew what the consequences would be. Nearly 50 years ago, when the prairie still had huge rice farms and was a major attraction for birders, the federal Soil Conservation Service warned that development “increases flood threat” to Houston.

In the early 1970s, developers looked at the prairie and saw a perfect spot for corporate offices, that later became the Energy Corridor, and an airport. The city of Houston bought land for the airport, which environmentalists and bird hunters spent a decade fighting in court, not only on behalf of the birds, but also to protect the prairie’s wetlands and prevent flooding. The city still owns the 1,400-acre site of the proposed airport, which it agreed to preserve to offset wetlands destroyed by construction at Bush Intercontinental Airport.

REDUCING FLOOD RISK: Gulf Coast native prairie, Houston’s original ecosystem, is nearly extinct — but conservationists won’t let it die

Environmentalists managed to stop some projects — the airport, a medical waste incinerator, and power lines — but not others, such as a section of the Grand Parkway.

Occasionally, the conservancy has benefited from development. Over the years, developers have donated acreage to offset their projects, in hopes of preventing lawsuits from environmental groups.

Today, the conservancy’s protected land is surrounded by growing master-planned communities, including Katy Sunterra, Bridgeland, Winward, Freeman Ranch by LGI Homes, Marvida and Elyson.

At Elyson, a 3,642-acre master-planned community expected to have 6,000 single family homes, the prairie itself has been mapped with street names such as Savannah Sparrow Lane and Tallgrass Meadow Trail. Homebuilders advertise a “beautiful way of life set among the wildflower(s) on 3,600 acres of pristine Katy Prairie.”

The Elyson development in Katy, photographed Thursday, Oct. 29, 2020. / Construction vehicles on the move on what used to be prairie land, Thursday, July 7, 2022, in Katy. (Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer)

“The thing that’s going to be interesting to me to see is once a lot of these developments are started, even though they have detention and retention requirements, a lot of them are building up four feet in order to protect their own subdivision,” said the conservancy’s longtime president Mary Anne Piacentini. “And it’s going to be very interesting to see how that’s going to impact downstream.”

Newland, the developer of Elyson, did not respond to requests for comment.

Nelson said the increased flood risk from development in the Katy prairie area will have serious consequences.

“I’ve worked with water all my life,” Nelson said. “And I just know that what they’re doing is going to be catastrophic some day.”

Regulation

To reduce their risk of flooding, the new homes are built higher up than older developments, typically atop fill dirt that has been trucked in.

Experts, however, do not agree on whether the new development increases the risk of downstream flooding, or even whether the new homes are in the floodplain.

Harris County Engineer Milton Rahman said the county does not allow people to build in the floodplain: “Unless you demonstrate this is out of the floodplain, they don’t get to build there.”

DEVELOPING STORM: For buyers within ‘flood pools,’ no warnings from developers, public officials

What that really means, however, is that if a developer uses fill to raise construction two feet above the 500-year flood level, the county does not consider the homes to be in the floodplain.

“I disagree with that characterization,” said Jim Blackburn, an environmental attorney and co-director of the Severe Storm Prediction, Education, & Evacuation from Disasters Center at Rice University. “If the building is in the floodplain, whether it’s above the floodplain or not, the people are living in the floodplain. When it floods, they may not be able to get to their house. Their cars will be flooded. The functional truth is they are in a floodplain. To say they’re not is, I think, to really obscure the whole issue that I’m trying to emphasize, which is it’s the water that we have to be focused on.”https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/PwiOS/2/

In the 100-year floodplain, the county does not allow fill, instead requiring new construction to be built on pier-and-beam or open foundation, with the finished floor two feet above the 500-year flood level.

In practice, however, the restrictions are more flexible. The county does allow new construction to be built in the 100-year floodplain on top of fill with a slab foundation, if it is offset by removing the same amount of fill from the site — typically by creating a detention pond — in compliance with the county’s “no net fill” philosophy.

‘THE WRONG MESSAGE’: Development tactic questioned in post-Harvey era

When it comes to new development, the Houston area has shown a limited willingness to meet the challenge of keeping people out of harm’s way. After Harvey, the city followed Harris County’s lead in passing rigorous elevation rules, requiring all new development in floodplains to be built two feet above the projected water level in a so-called 500-year storm. Houstonians still can build in the highest risk areas after landowners won a 2008 lawsuit to overturn a city ban on development in the floodway.

Harris County Precinct 3 Commissioner Tom Ramsey, a drainage engineer whose precinct includes the Katy Prairie, said building requirements have been fully offsetting the impact of new development since the county strengthened the criteria in 2009: “If you look at the 75,000 homes that were built after 2009, only 460 homes were flooded in Harvey. That’s an amazing accomplishment, in my opinion.”

New development is not the problem, Ramsey said.

“The problem is old development,” he said. “It’s very clear, very well documented, that new development is not causing impacts downstream. That’s just a myth. The problem is, we did not have enhanced regulatory requirements prior to 1984.”

However, based on the severe storms that have occurred in recent years and are expected to worsen with climate change, some say new development could continue to cause downstream flooding if regulations do not account for increasingly larger rainfalls.

Higher rainfall forecasts

One reason why developers are required to incorporate more flood mitigation now is because of higher rainfall estimates calculated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration using historical data for the Houston region. In the years since Harvey, NOAA has updated rainfall estimates to include data through 2017. Its formula does not take into account projections for how climate change will impact future storms.

‘A WARMING WORLD’: Tired of Houston’s heavy rain? Climate change means you should probably get used to it.

In Harris County, the agency now recommends local governments plan for 17 inches of rain in 24 hours instead of the previous standard of 13.2 inches to protect against what it considers a 100-year storm. Its estimate of a 500-year storm has gone up from 18.9 inches to 25 inches. The city of Houston and Harris County, among others, have made that change.

Despite its name, a 100-year storm is not a downpour that is expected to occur once every 100 years; its accepted definition is a storm that has a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year. In other words, a 100-year storm could occur several years in a row.

Larry Dunbar, an engineer and consultant for Fort Bend County who worked on developing the county’s drainage regulations, said the Houston area should be designing new development to withstand more than 17 inches of rain in a 24-hour period.

Environmental attorney Jim Blackburn agrees, pointing out that it is not unusual for Houston to get 20 to 24 inches in 24 hours.

Tropical Storm Allison dropped 26 inches of rain in some parts of town in 2001, Tropical Storm Imelda exceeded 29 inches over three days in 2019, and Hurricane Harvey dropped 25-40 inches with a maximum rainfall total in Harris County of 47 inches over a four-day period.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/IQlv1/1/

Texas State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon said he believes the new numbers “will be fine for a while in the Houston area despite climate change.”

HARVEY’S WAKE SERIES: How Harvey transformed resilient Meyerland, from modest 1950s homes to raised mini-mansions

Underestimating potential rainfall would allow developers to continue expanding into the prairie, particularly since they are only liable under state law for flooding that occurs within 10 years of completion of a project.

“Doesn’t matter how bad they screwed up, makes no difference,” said Dunbar, who is an engineer and an attorney. “Engineers and developers kind of hold their breath for 10 years after they finish their work, and hope it doesn’t flood. Then they’re home free.”https://www.houstonchronicle.com/projects/2022/hc-floodplain-res-permits/

On HoustonChronicle.com: Kingwood residents file suit after hundreds of homes damaged during May floods

Using accurate rainfall estimates matters even more when trying to offset the impacts of large-scale projects, such as the proposed Highway 36A, which could cut through prairie land and further accelerate development in the area.

Wetlands

The conservancy has around 5,000 acres of wetlands, though that does not necessarily mean they would be protected from a possible highway.

Wetlands have a slippery definition when it comes to development. The Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for approving permits to build on wetlands and determining whether land meets the federal government’s definition, which changes frequently but often does not protect the type of wetlands on the Katy prairie.

“There are wetlands that are not protected because they’re not close enough to a flowing water body,” Blackburn said. “So there’s a lot of wetlands that are being developed that are technically scientifically wetlands, but they don’t legally qualify as wetlands.”

In February, the Corps determined the Bridgeland master-planned community could build on 112 acres of wetlands — it deemed the wetlands were not protected under the federal definition — and the agency currently is reviewing a Bridgeland request to build on another 155 acres of wetlands.

Asked if developers have to do more flood mitigation when they build over prairie or wetlands, Rahman, the Harris County engineer, said that is not really an issue, since developers are not allowed to build over wetlands.

“If it’s a wetland — like Katy Prairie, a majority of them — you’re not even allowed to build there,” Rahman said.

COASTAL BARRIER: Crushed turtles and shrinking wetlands: How the proposed Ike Dike could affect wildlife and plants

However, he said, the definition of wetland by the federal government may be too limited.

“There definitely needs to be an option to look under the hood, why we are able to develop and why this land is getting reduced,” Rahman said. “So, perhaps there’s the regulation that has shortcoming.”

Kristen Schlemmer, legal director of the nonprofit Bayou City Waterkeeper, has no doubt people are building on wetlands. The organization has a program that helps residents monitor and report construction in wetlands.

“If you start building a lot in it, which it looks like that’s happening, you end up losing that flood retention and that water has nowhere to go but downstream in areas that, as we saw during Harvey, can have the potential to flood a lot,” Schlemmer said.

When a developer gets a permit to destroy wetlands, it is supposed to offset the damage, often by creating or maintaining wetlands nearby or at another location.

“So, there are people who have filled in wetlands, and then they’ve protected a wetland someplace else,” Piacentini, the director of the conservancy, said. “As long as there’s no net loss of wetlands, that meets the requirements of the law. Is it the best way to do it? Probably not, but that’s the law. And if they’re following the law, you can’t blame them.”

Overall, the current approach to deciding where to develop in the Houston area still is moving toward a “death by a thousand cuts,” according to Sam Brody, director of the Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas at Texas A&M University at Galveston.

“It’s not just pavement, but it’s altering drainage patterns,” Brody said. “It’s altering naturally occurring wetlands, which is a big part of our research. It’s so important to maintain those, and you can’t just replace them elsewhere and expect the same level of ecological integrity or flood reduction.”

Regional planning

Spreading across Waller and Harris counties and a pair of watersheds — Upper Cypress Creek and Addicks Reservoir — the Katy prairie is an example of why experts say local leaders must plan on a regional level, rather than managing development and flood risk on a county or city level, especially with climate change producing heavier storms.

“The way we’re going about it right now, that when you design detention, it’s a parcel-level, or development-level situation. It’s runoff off of that site,” Brody said. “It’s not looking at the accumulation of 100,000 other runoff events surrounding it. It’s not looking at the roadway or infrastructure servicing that development, or people’s back yards and what they’re doing.”

INSIDE LOOK: San Antonio has a hidden downtown flood tunnel. Could Houston build one even bigger and bolder?

Nelson, the former rice farmer, said it is too late to avoid the flooding consequences of development in the area and the risk will continue to increase.

“The serious thing is they haven’t stopped. They’re still buying land. They spend an outrageous amount of money elevating it, digging big holes and building it up. And they continue to move north and west,” Nelson said. “Well, my question is, what’s going to happen when we get another Harvey?”

HARVEY’S WAKE

Five years after Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Texas coast and inundated the Houston region, there is trauma, recovery and frustration. Over the week of the anniversary of the storm, the Chronicle assesses the damage and the progress in a eight-part series.

Written By

Jen Rice is a reporter for the Houston Chronicle covering Harris County government. A native Houstonian, Jen graduated from Barnard College at Columbia University and earned a master’s degree from University of Texas at Austin’s LBJ School of Public Affairs. Before coming to the Chronicle, Jen spent three years covering City Hall for Houston’s NPR station. Her reporting has aired nationally on NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered and Here & Now.